I went to a live pitch event with Raw Fury’s CEO Pim Holfve and Head of Scouting Johan Toresson, arranged by Games Denmark and generously hosted by Raw Power Games. Ten different teams pitched their games, and received feedback from Pim and Johan on their pitches.

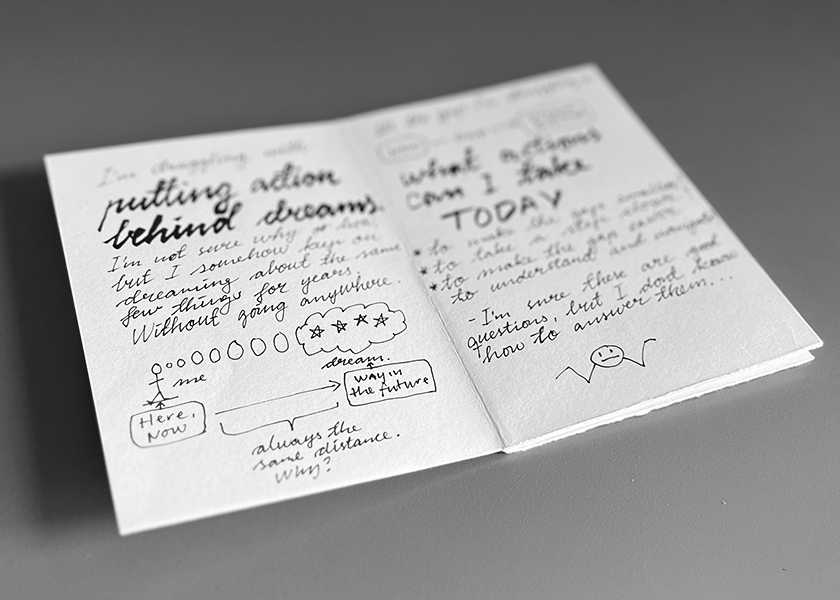

Pitching is hard, but it’s a skill that can be taught and learned. The painful thing about it, is that you have to get it wrong a lot of times before you get it right. So it was great to experience 10 teams pitching 10 very different games, and mostly doing a great job.

Here are some of my takeaways from Johan and Pim’s feedback:

Focus on player’s play styles rather than their demographics. Paint a clear picture of the player type in terms of other preferred games, social media habits, media consumption etc.

Show comparable titles and how your game differs. Simply showing Risk of Rain II and Hades as references when pitching your roguelike is not enough. Explain how your game is different and where it excels in comparison.

Have design pillars. What are the absolutely essential design pillars that your game is built upon? What do you want the player to feel and do? What is the mood?

Show how gameplay can deliver on your design pillars. “We’re making Star Wars meets South Park” - Great. What are the mechanics?

Have clear player verbs. Know what players will be doing in your game. Show it clearly in your pitch.

Have articulated USP’s. By articulating your game’s unique selling points, you demonstrate that you know your audience, your genre and your game.

Show gameplay. Maybe even have an appendix where you go through it in detail.

Show how the publisher fits in. Be clear on what you need from a publisher, and how you see them fit in a partnership around your project.

Show that you’re thinking about value creation for your partners. Make sure that interests are aligned, and there is room for every partner to make money.

Think about how to do fun shit for Twitch - “Not enough people think about how to do fun shit for twitch” as Johan eloquently put it.

What kind of pre-knowns do we assume from the player? Does our game build on something approachable, or do we assume that players are familiar with the cricket score system or the finer nuances of archeology?

Sales projections are nice. But make sure that you base those projections on comparable titles and not on the outliers of the genre.

Skip numbers unless they’re really clear. “As soon as there is numbers, I’ll check them in my head” as Pim pointed out. Attention goes away from what you’re saying, unless the numbers are clear and obviously match up.

Live pitch ≠ mail-out pitch. Use way less text in your live pitch slides than you would in your mail-out slides. People listening to your pitch shouldn’t be distracted by dense and wordy slides.

You only get one launch. “Can we just skip fucking early access?” Johan said. Early Access is the launch. The demo is the new Early Access.

I’ve revisited my Indie Games Business Case Template and made a few additions and adjustments here and there in order to incorporate the notes above. The goal of the template is to make it easier and faster to build a compelling pitch and business case.